Everything* as code

Hello, dear visitor. Seeing you here today means you're likely a developer, engineer, coder, or some combination of these -- and that you're familiar with the term "code". For several decades engineers all over the world were writing code. This code, first and foremost, was meant to solve problems. And today I would like to tell you about solving even more problems with the power of code. I will show you why and how we should use code for more and more scenarios across our professional and personal lives.

Information as code #

Before diving into 21st century, let's step back and consider what "code" really means. Today, we use it for programming, automation, and infrastructure, but the idea of encoding information in a structured, repeatable way has been around for centuries.

What comes to mind when you hear the word "code"? Most of us (myself included) immediately think of a programming language.

But the word "code" wasn't originally popularized by programmers. Long before computers existed, humans developed ways to encode information, often to preserve knowledge, communicate securely. One of the earliest examples comes from cryptography.

Cryptography is one of my many interests. Ciphers, cryptography algorithms, encryption, all that jazz. The practice of encoding information goes back to Ancient Egypt, but one of the earliest well-known encryption methods is Caesar's Cipher (also called Caesar's Code).

Caesar's Cipher is a simple technique: shifting letters forward in the alphabet to obscure the original message, making it unreadable to anyone who doesn't know the shift pattern. The result? Encoded information. Information hidden as (somewhat) code.

At its core, this is the same principle that modern software engineering follows. We structure information in standardized formats so it can be stored, processed, and used reliably. Whether it's YAML configurations, JSON APIs, or structured documentation, we encode information in ways that make it easy to retrieve, automate, and keep track of.

Logic as code #

Now let's get back to our time.

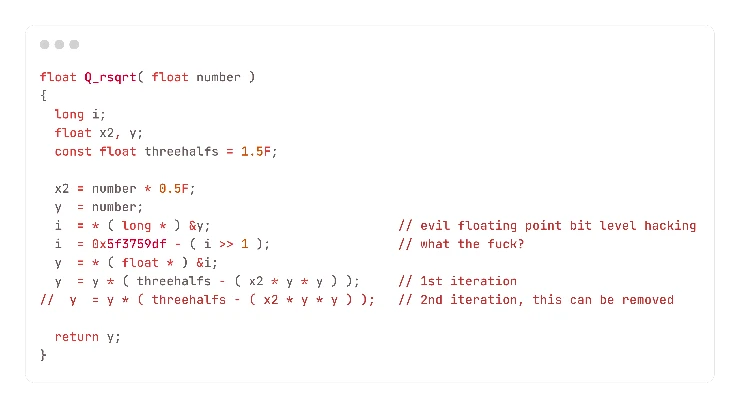

Programmers have been writing software at least since 1940. This software is meant to solve different problems: calculate the sum of two numbers, print "Hello World", launch people in space and send memes to your friends. What all these examples have in common? They encapsulate the logic. An algorithm that describes an order of actions to achieve the necessary result.

Indifferent to complexity, all software is alike in this regard. They have an input: be that a number, a certain trigger, a file. They have from one to infinity steps in their core process, each of which performs a certain action. And they have an output: a rocket engine that's starting, a package with part of a meme flying over fiber optics, or a number.

And the logic presented in this very part is described via code.

Why is it this way?

Disclaimer

I'm not describing the history of programming languages here, I'm sharing my thoughts on the topic in general.

Thinking rocks (computers) think in a certain way. In a very structured way. In a way that is predictable and repeatable. The same way the code that is written for these computers have to be predictable and repeatable. This way, we can make sure that, unlike meat people, when a computer is asked to run "Hello World" a million times, it will do exactly that -- and not complain on the 10th repetition that "This is pointless" or "Go hello yourself".

Making logic structured, reliable, repeatable helps people offload some of mental capacity on other things. For example, write more code! Create games! Or learn how to play violin!

Configuration as code #

Time goes on, and so is progress. And us. And complexity. Complexity above all.

Writing increasingly complex software introduced new challenges. Instead of handling a single task per program, developers started teaching software to execute multiple tasks. Fast-forward several decades, and we now have "everything apps" that do, well, almost everything. Industrial revolution was a mistake.

But I got off the track.

The increasing complexity of software led to the implementation of configuration management. As I'm sure all of you know, configuration is a process of configuring (duh!) a software to work in a certain way: use certain amount of resources, store the output in a certain directory and write log in a specific file.

Okay, so far so good.

Let's take the most basic program on a Linux machine: (my precious) bash.

How many configuration files this program has, how do you think? The answer is, well, at least four.

- /etc/profile

- /etc/bashrc

- ~/.bashrc

- ~/.profile

Okay, to be honest, this is not the simplest example: majority of programs try to keep all configuration in one file.

But modern operating systems do not end on one program. They have hundreds of them. And almost every one of them have a configuration file.

And, let's be honest, we don't usually work on one system. We use multiple. In systems administration and infrastructure management we have tens, hundreds, thousands of them. Each has hundreds of programs, most with at least one configuration file. See where I'm getting here?

So did the incredible people who thought about this issue and introduced systems to solve this problem. Namely, configuration management services. Here comes the concept "Configuration as code".

As well as in a previous part, this concept had to have the same qualities: structure, reliability, repeatability.

We need structure, because sometimes we want software to be configured in a certain way and in a certain order. For example, first we want to install nginx on a server, and only after we want to install go backend application.

We need reliability, because we want to make sure that once started, the process will be finished and configure the managed software in the exact way as we described it to be configured.

And, of course, we want reproducibility, because we don't want to see ourselves in a situation when 50% of API servers are configured properly, and other 50% are slacking and not listening to incoming requests.

As you might know, the way aforementioned software works, may be different. But regardless of the working model, the end result will be similar. But, of course, in order to achieve this result, it is our job to write the instructions for the configuration management software properly and accurately.

Infrastructure as code #

Increasing complexity introduces requirements for simplification. Sometimes this simplification comes from removing unnecessary elements of the system. Sometimes it comes from rebuilding the whole system from the ground up. And sometimes -- from hiding it behind the abstraction.

What if instead of necessity to administer our own servers and racks and datacenters, we handled these chores to someone else, leaving us with only SSH port to our so called "server".

Please welcome, cloud infrastructure providers.

Cloud providers offloaded some work from our shoulders, allowing us to focus on more important tasks:

writing softwarespend time with friends and family- managing cloud infrastructure through the console

- paying bills

Turning hardware entities (servers, network routers, etc.) into software created new opportunities. If it's software, it can be handled like any other program. It can be automated, it can be combined with other elements, it can be tracked and monitored and described as a code.

Yes, I'm talking about infrastructure as code.

I must say, AWS did an amazing good job at creating the problem and then selling a solution to this problem. Yes, I know, CloudFormation is free, but when something is free you're the one that's the product (ha-ha).

Tools like CloudFormation and Terraform changed the game drastically. Now, instead of spending countless hours on setting up virtual machines, keeping track of them, monitoring and updating their parameters, we describe all that we need only once and repeat indefinitely (until we have enough money).

Personally, I love IaC because I remember all the difficulties installing hundreds or so of new servers. The countless hours, the blood, the pain. And now all I have to do is copy-paste code from documentation and run apply. Marvellous! It almost feels like comparison between my old cassette Walkman and Spotify: one you had to manually insert the tape, switch sides, rewind, play, and the other is just a "Tap to enjoy".

Intermission #

I've been speaking about code for several chapters now, but I haven't touched on what ties it all together. And it's not the code. Well, not only the code. In the end, code is just text. Same as this article, same as this website. It's just a text in one way or another.

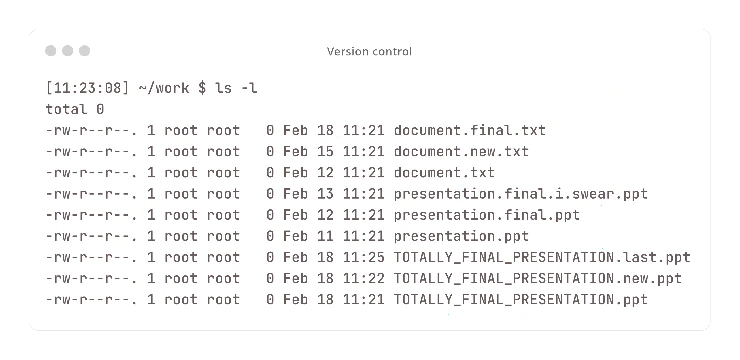

I can imagine many of you, like me, kept track of some text files in a way like this.

This was long before I started working in IT. But you know what? This also was a version control system of sorts. Though it is not actually a system, it served the same function: keeping track of changes.

Yes, VCS is the MVP.

The advantages of VCS in general and git specifically has been stated numerous times, but I can't overstate how crucial it is to use it in our job. The reasons are simple. Git is a software, and software doesn't lie.

A developer pushed a buggy code to a software, and when everything broke, nobody stepped forward claiming the guilt for this code. But we know. We have git. We have linear history. Over the past few months, our AWS bill doubled. Why? Who knows? Git knows. We can find that several months ago a systems engineer made a typo and rolled out 20 ec2 instances instead of 10.

Git brought us lots of fun activities as well! With the help of git we can have:

- merge conflicts

- branching strategies

- code reviews

- release branches

- more merge conflicts

- force pushes

- and many more!

The linear history of VCS allows us to be sure that always the latest change will be delivered where we want it to: a latest configuration file, a latest infrastructure setup, or the latest publication in a blog.

And if the latest is erroneous, we always can roll back to a previous commit.

Observability as code #

So far we have discussed mainly software and hardware. It is, in the end, the heavy lifter of all the modern internet and our presence here as well.

Let's imagine a situation. A team from our company released a new feature. It was in development for a long time and it is a big requested feature. And also quite resource heavy one. But how can we be sure that after the release the CPU usage on our machines is not through the roof? How can we be sure that after the release pages of our website are not loading for several seconds?

That's correct. The monitoring.

There is no DevOps without monitoring. There is no SRE without the reliability. You get the idea.

Something as crucial as system health monitoring must be set in stone.

Funny story, actually. The idea for this whole article came to me naturally after I accidentally destroyed managed Grafana instance on AWS with all the configurations and dashboards. Unfortunately, all the dashboards were lost for good, as I didn't yet transferred them into git. So here's a lesson for you folks: if something is not in git, it does not exist.

Observability is not a single element in the system. It consists of at least three components.

-

A tool that gathers data: metrics, logs, and traces.

The scraping tool is usually a daemon that queries endpoints or log files and sends this data to the next element in the system. As a simple application it can be set up via configuration management tool pretty easily.

Examples include, but not limited to: Amazon CloudWatch Agent, Grafana Agent, Logstash, Prometheus Node Exporter.

-

A tool that collects this data and performs certain operations on it: aggregates, combines, calculates and stores.

The software that gathers and manages this data is the heavy lifter in this system. Gathering terabytes of data and making sense of it is not an easy task. Properly configure it is a mastery by itself.

Examples include, but not limited to: Amazon CloudWatch, Grafana Mimir, Elasticsearch.

-

And a tool that shows all these numbers to the end user: a dashboard or a message in a messenger.

And the last, but not least, is the thing why we even bother with all this stuff. The Dashboard. The graphs. The thing that arouses managers and directors all over the world. I would lie if I say that I don't like them, because I do.

Examples include, but not limited to: Amazon CloudWatch, Grafana, Kibana, Splunk.

And I must say, the developers of these tools did a marvelous job at allowing us, system engineers, to configure the software via the code. Can you imagine recreating all this manually each time you fuck up the Terraform deployment?

Instead, we have a blessed possibility to just copy several thousand something JSON into the repository and never have to do it ever again. Thank you, developers, for reproducibility!

And also we can automate the whole stack! A dozen new VMs appeared in our infrastructure? No worries! Templated configuration will be deployed to them with the new commit and in a matter of minutes we will see the metrics and logs from freshly installed application.

Documentation as code #

We discussed today a lot of technical elements of various systems. It only makes sense, because we, in the end, are developers. We work with the software, we write software, we operate software.

But what developers don't like to do?

I think it's safe to say that most of us don't write documentation. At least, not as much as we should write.

What comes to your mind when you think about documentation?

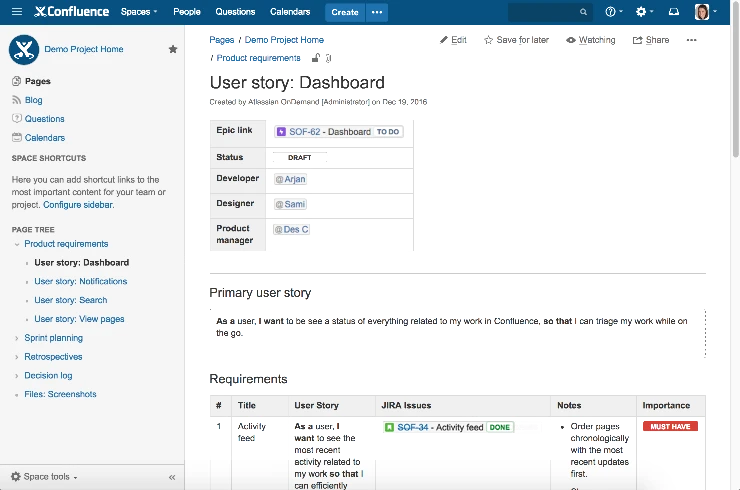

Confluence. This is what I think of the most. And gods I hate this thing.

I know it's a de-facto standard place to keep things documented. But has anyone here actually seen tidy, organized, up-to-date documentation in Confluence across an entire company? I think I have never.

But what if I say to you that it is possible to make documentation bearable, helpful, fast and current? We won't even have to learn a new skill, because we already know how to write code. All we have to do is write the same words, but in English (or Polish, or any other language).

This text, this article, and consequently this web page, are written in markdown using Obsidian. The same way as I write my personal notes. The same way as I write readmes for modules in Terraform and Ansible. The same way we may utilize the power of markdown and numerous static site generators (e.g. Material for Markdown, Jekyll, 11ty etc.) to create our internal project documentation.

This approach opens several opportunities for us.

- It is faster. You write documentation in the same place you write your code: Vim, IDE, Notepad. You don't have to open a bloated confluence webpage and wait for minutes to open the editor.

- It is current. You commit a new page to the repository, and in several minutes, all other developers will have access to it.

- It can be accessed offline. I know, in modern always-connected reality, it's kinda obsolete necessity, but

back in my daysthere are situations when you may not have access to the internet and you might find something in the documentation. Git saves the day! Fetch all the latest documentation updates and hop on the airplane -- you will have the documentation with you even without the internet! Given that it's still just text, you can open it in your favorite IDE right next to the code. - It can be automated. The biggest pain in the ass for me after the bloat of the Confluence is the fact that it's getting obsolete very fast. It's impossible to keep track of everything in the documentation and constantly asking colleagues if this page is current of this service does not even exist already. Instead, we can set up a script that will (for example) query the list of database endpoints and paste it to corresponding documentation page automatically. This is just one of the examples, I'm sure there can be many more.

Epilogue #

You might have noticed that the title of this talk has an asterisk in it. I bet you forgot about it, as did I writing this article. The thing is, not everything is meant to be described as code.

Let's take human interaction in general. Yes, it can be repetitive, yes, it may be structured in a certain way. But the genuine joy and meaning behind these actions is what makes it priceless. Friends are so much more than just a recipient of our information. You can't substitute in-person communication with swipes left or right with the same effectiveness.

Or, for example, relationship in particular. Ask my wife. She's usually not very happy when I talk to her as a machine and not a human being. "Sometimes you produce sentences so clear and so optimized, it creates a feeling I'm talking to a robot." Another example: sometimes I produce a step-by-step course of action for certain problems when all that was needed from me is just to listen and to comfort her. Not provide a solution for a problem, just be there for her.

Earlier I talked about documentation as code and it's benefits. You know what is an opposite of this approach? Code as documentation. I heard several times statements that good code is like documentation. But let's be honest, how many times have you actually seen the code that good? The only example that comes to my mind is, surprisingly, Terraform code: it is so well structured and declarative in it's nature, that it's quite natural to understand it as a document describing the infrastructure.

When I started writing this article, I wasn't sure how many examples I would come up with or how I would connect them all. In the end, the topics are quite different. But they do share the same approach: they can be (and are) represented as code. As the previous sections showed, implementing this approach saves us time and mental capacity -- not just for us, but for the people we work with and work for as well. And money, of course.

I hope I encouraged at least one or two of you all to think about your work in this way: "Can it be presented as code? Can I automate it? Can I make it work by itself while I spend my time on something more pleasant?" Because if the process is structured, reliable and repeatable, it does sound like an algorithm a lot. And you know what that means.